This essay was written by Ladybee in Winter of 2006, and published as the feature article of Issue 57 of Raw Vision, the world’s leading journal of outsider art.

Reconnecting Art & Life

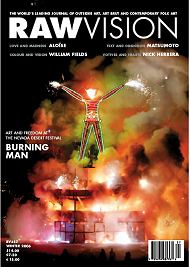

Burning Man, an annual temporary community in the Black Rock Desert of Nevada, is the world’s largest outdoor art gallery, featuring nearly three hundred art installations scattered across a barren, prehistoric lake bed known as a playa. For one week late in August of each year, nearly 40,000 participants gather to create a vibrant city based on self-expression, survival, sharing, and radical self-reliance. Life in Black Rock City is characterized by collaborative interactive art-making, gift-giving, performance, and costuming. The making of art is encouraged; anyone can display whatever they’ve created without judgement, competition, or censorship. Art is a vital part of the city; it is virtually everywhere – on the open playa, in the camping area, in the center café, along the trash fence which marks the boundaries of the city, in the small participant-run airport, along the entrance road, and within a pavilion on which stands the Burning Man, a 40’ tall wooden figure that marks the center of the city, and is burned at the end of the event. The art is characterized by interactivity; it’s accessible, hands-on, and meant to be touched, climbed, and played with, providing intense, intimate experiences not usually available in gallery or museum settings.

Here, art is not viewed as the sole province of trained, educated specialists, as it is in the institutionalized world; it is part and parcel of everyday life for the citizens of Black Rock City, nearly all of whom produce objects for use and display during the event, from costumes and small items given out as gifts to large-scale art installations. Art-making in this way seems related to earlier societies, where decorating one’s possessions and making objects was a natural expression of belonging to a group, and a way of making daily life meaningful. At Burning Man, the do-it-yourself ethic is the community standard, and aesthetics are enthusiastically explored by everyone, not just artists.

Neither is art viewed as the work of the isolated individual; virtually all of the larger works at Burning Man are produced collaboratively, bringing artists, crews, and participants together in a rich, immersive and immediate experience. This kind of empathic social interaction through art-making generates community on the playa and beyond, as participants return to their homes and create their own regional events in the style of Burning Man. There are currently 65 regional groups worldwide. In addition, Burning Man’s sister organization, the Black Rock Arts Foundation, funds interactive art outside of the event, much of which is made by untrained artists. This unusual situation has inspired engineers, teachers, techno-geeks, scientists, community groups, doctors, graduate students, carpenters – all sorts of people who would not consider themselves artists – to make art, many for the first time.

Steve Heck is a piano mover from Oakland, California, who saves all of the piano parts he acquires in his work, storing them in his crowded warehouse. At Burning Man 1996 he built a two-story enclosure entirely from piano soundboards and casings – 88, to be exact – the number of keys on a piano. Participants continuously played the exposed strings of the soundboards.

From 1996 to 1999, Burning Man participants were treated to unconventional folk operas performed on elaborate, fanciful architectural fantasies built by San Franciscan Pepe Ozan. In the early 1990’s Pepe, born in Argentina and trained as a lawyer, started making playa mud lingams which functioned as chimneys. By 1996 these had evolved into complex structures with multiple towers and platforms upon which the operas took place, complete with an orchestra, a libretto, singers and costumed performers, and culminating in fire.